How Mitsunobu Koshiba became the youngest president in a conservative chemical industry in Japan?

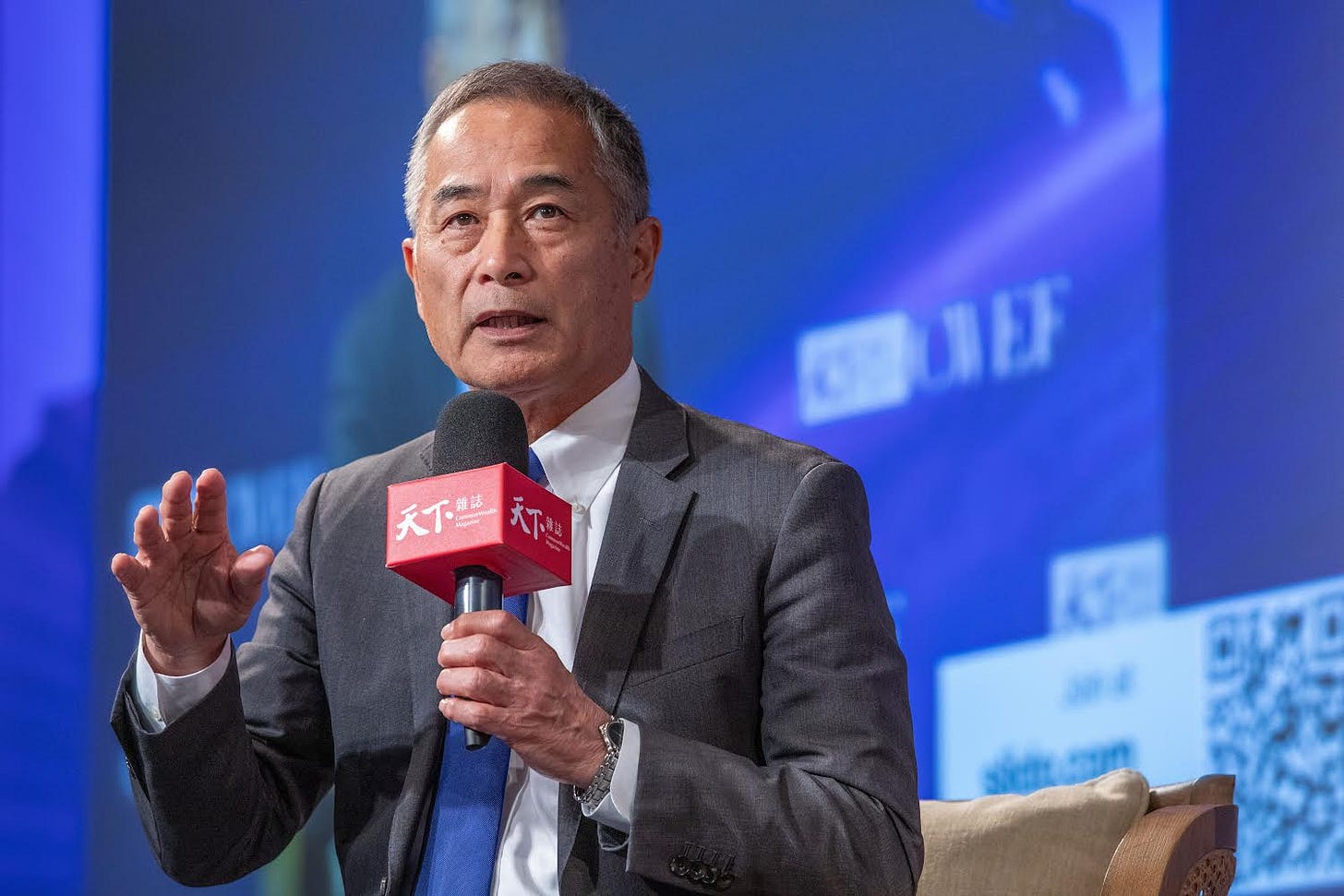

Liang-rong Chen

Source: Chien-Tong Wang

After enduring the “Lost Three Decades,” Japan’s once-glorious semiconductor manufacturing industry has lost its global influence. Yet, Japanese companies now dominate critical semiconductor materials, such as photoresists, etching liquids, and substrate materials. Why is this anomaly possible, especially without the protection of major domestic manufacturers?

This peculiar phenomenon has intrigued me for years.

Finally, I had the opportunity to uncover the mystery with the help of Mitsunobu Koshiba, a legendary figure in Japan’s chemical industry and the 70-year-old former chairman of JSR, a leading Japanese photoresist manufacturer. In January, Koshiba delivered a speech at the CommonWealth Economic Forum and agreed to an interview with me.

Koshiba, during his tenure as JSR’s president, collaborated with TSMC and ASML to co-develop Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) photoresists, maintaining a market share of over 50% for an extended period. Photoresists are essential materials in semiconductor lithography, used to etch transistor circuit patterns.

EUV photoresist, in particular, is the most expensive chemical material in the field, priced at over $5,000 per liter.

JSR’s critical role in the semiconductor industry sparked interest from Germany’s Merck Group, which reportedly considered acquiring the company. In response, Japan’s state-backed Japan Investment Corporation (JIC) acted swiftly in 2023, acquiring JSR for nearly NT$200 billion and delisting it. The move caused a significant stir in the global semiconductor industry.

“But our market share kept declining,” Koshiba remarked with a wry smile. After JSR’s “quasi-nationalization,” some clients began shifting orders to other suppliers, fearing that proprietary technologies might leak to Rapidus, the Japanese government-backed wafer foundry. “To make matters worse, I even became a director at Rapidus, which made the situation even more awkward,” he added.

Koshiba, who spent 12 years in the United States, is fluent in English and communicates in a straightforward, candid manner uncommon for a Japanese executive. Occasionally, his conversations are peppered with English expletives.

Originally a photoresist R&D engineer, Koshiba’s experience studying materials science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison proved pivotal. In the 1990s, JSR’s then-president tasked him with establishing a subsidiary in Silicon Valley, where he successfully captured the U.S. market.

This achievement led to his promotion as president at the age of 53—an exceptionally young age in Japan’s conservative chemical industry. “I was the youngest,” Koshiba said proudly, noting that the electronics division he managed accounted for 80% of JSR’s profits.

For Taiwanese companies aspiring to enter the semiconductor materials and equipment industries, one significant barrier is impossible to ignore: TSMC’s rigorous supplier standards. The company is unlikely to switch to new suppliers simply to save costs, as the potential consequences of process disruptions are astronomical. So, how can new entrants overcome this hurdle?

Koshiba outlined three critical strategies:

1. Focus on Next-Generation Technology.

“Always target the next generation of technology,” Koshiba advised. This philosophy of “overtaking on the curve” drove his decision to bypass KrF excimer lasers and instead develop photoresists for ArF lasers, a next-generation technology. Even after JSR became an industry leader, Koshiba understood that competitors could still disrupt their position with newer technologies. This motivated him to double down on advanced EUV R&D, ultimately securing JSR’s leadership position.

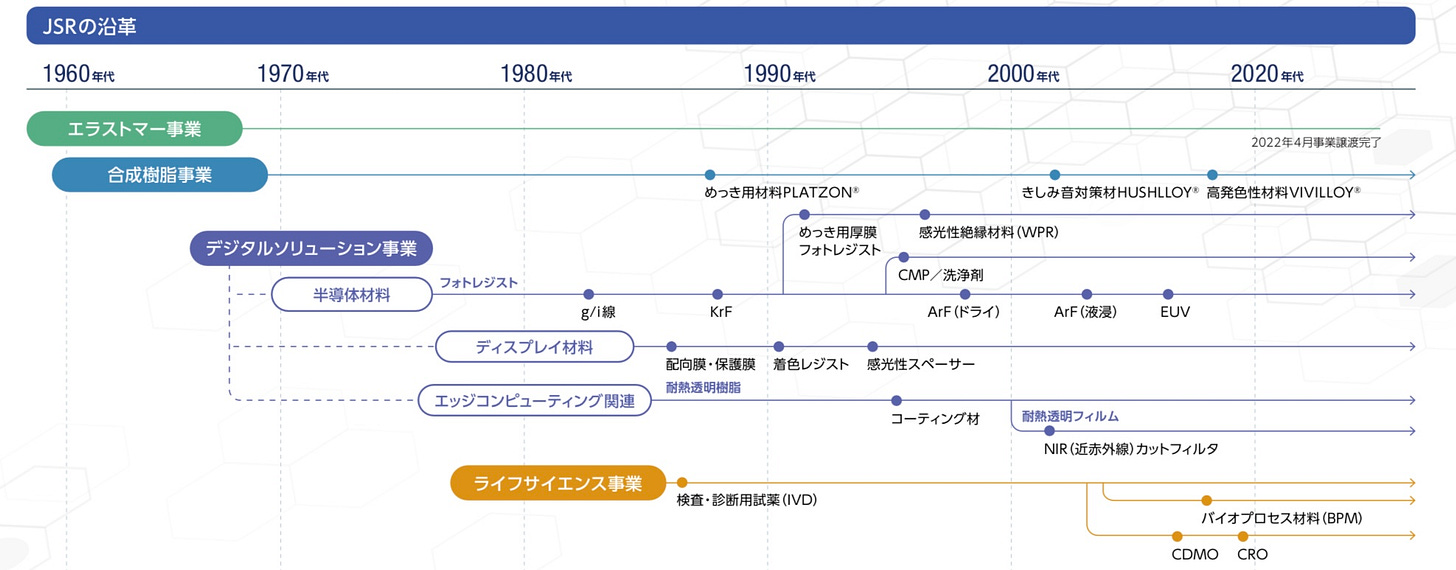

JSR started to develop semiconductor material in the 1970s. Koshiba decided to bypass KrF excimer lasers and go for the next-generation ArF lasers instead. Source: JSR corporate profile.

2. Timing is Everything.

Koshiba’s assignment to the United States coincided with the “Japan Number One” era, when companies like Hitachi and NEC were on the rise. Curious about Japanese innovations, American companies were more willing to experiment with new materials. Additionally, as U.S. semiconductor manufacturers struggled and their production lines sat idle, engineers had more time and freedom to test new formulations.

3. Be Ready When Opportunity Knocks.

“You never know when opportunities will come, but when they do, you must be ready,” Koshiba emphasized. In early days, American manufacturer relied entirely on domestically produced materials. Koshiba recalled a critical moment when Motorola faced issues with its supplier Shipley’s photoresist. In a crisis, Motorola executives reached out to Koshiba, who resolved the problem within two days. This swift action solidified JSR’s status as Motorola’s exclusive supplier.

Koshiba’s technical expertise was undoubtedly a key factor, but his ability to build deep client relationships was equally vital in securing pivotal opportunities.

Yen Tao-Nan, a former head of TSMC’s EUV R&D and now vice president of R&D at ASML, vividly recalled Koshiba’s foresight. “He had remarkable vision. Back then, I was just starting out,” said Yen, who met Koshiba as a young engineer at Texas Instruments (TI) in Dallas. Koshiba had stationed personnel at TI’s headquarters with the sole purpose of fostering relationships with engineers in charge of the most advanced lithography like Yen.

Reflecting on those times, Koshiba joked, “All I wanted was for them to try our photoresists.”

In the early 2000s, immersion lithography emerged as a disruptive force, altering the technology landscape and prompting many photoresist manufacturers to pivot their R&D focus. However, JSR was the sole company that remained committed to EUV, continuously refining its formulas and delivering samples to support TSMC’s EUV development. “At that point, JSR was the only partner we could rely on,” Yen said.

Despite widespread skepticism about EUV’s viability, Koshiba’s deep technical insight allowed him to persevere. As a graduate of Chiba University, a hub for photomaterial research, Koshiba drew on decades of hands-on experience to address technical challenges.

Koshiba shared a story from a pivotal board meeting. When he proposed investing in EUV, a board member who was also the CEO of Nikon, a major lithography equipment manufacturer, voiced opposition. Nikon’s research suggested that producing EUV photoresists was theoretically impossible. Koshiba firmly disagreed.

“You’re wrong,” he retorted.

Koshiba explained that Nikon’s experiments were flawed due to insufficient EUV light source power, which resulted in too few photons and statistical errors in their conclusions. Drawing on his decades of practical experience in photoresist chemistry, he argued that these challenges could be overcome with specialized design solutions. Ultimately, the results vindicated Koshiba’s judgment.

A Taiwanese chemical R&D executive described Koshiba as his idol. “It’s incredibly rare for someone with an R&D background to become a CEO in Japan’s chemical industry,” he said, attributing this to the traditional dominance of Japan’s trading houses in industrial leadership.

Last year, during CommonWealth Magazine’s reporting trip to Japan, our team was surprised to discover that several presidents of major semiconductor supply chain companies had backgrounds in law or business studies and came from marketing, unlike in Taiwan, where most leaders are exclusively engineers.

JSR’s unique corporate history may have also contributed to Koshiba’s rise. Originally founded as Japan Synthetic Rubber Co. after World War II, the company was established to import synthetic rubber technology. Initially, the Japanese government held a 40% stake, and Bridgestone, a tire manufacturing giant, was also a major shareholder for a period.

When Koshiba visited Taiwan as JSR’s president, his first stop was always TSMC, followed by Cheng Shin Rubber in Changhua.

In the 1980s, as JSR pivoted from bulk chemicals to semiconductor specialty materials, it faced significant challenges. Japan’s semiconductor giants often had in-house suppliers within their corporate groups. For example, Hitachi maintained close ties with Tokyo Ohka Kogyo (TOK). As an independent company, JSR had no such advantage and had to carve out a foothold in the U.S. market—a backdrop that explains why Koshiba was entrusted with heavy responsibilities early in his career.

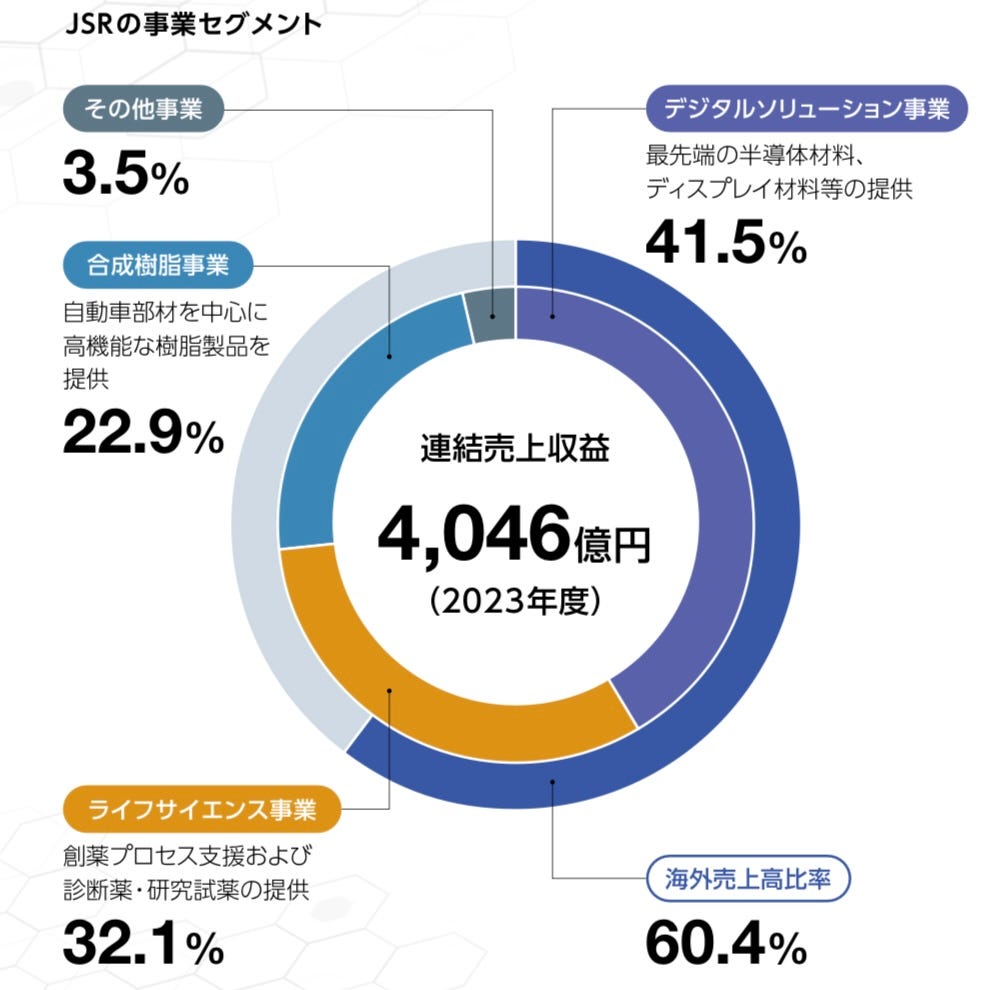

For JSR total sales revenue, 41.5% came from digital solutions including semiconductor and display materials. Resins and life science departments are 22.9% and 32.1%, respectively, of the total revenue. And sales overseas takes up about 60%. Source: JSR corporate profile

Today, semiconductor materials are a fiercely competitive battleground. Global giants like Merck and DuPont have made major moves to expand their presence in the field. How has JSR managed to stay ahead? Koshiba credited Japan’s network of small and medium-sized suppliers, which he described as unrivaled in quality. “Without them, we wouldn’t be this strong,” he said.

Photoresist is composed of three primary components: photosensitive materials, resins, and solvents. And the three combined consist of seven to eight subcomponents, which JSR sources from a variety of suppliers. By contrast, vertically integrated chemical conglomerates like DuPont produce these materials internally.

While this approach might seem more efficient, a manager at supplier of chemicals for TSMC pointed out to me that large conglomerates often overlook small-volume semiconductor material requirements, prioritizing their larger, more profitable divisions instead. This lack of focus results in slower response times and fewer resources for semiconductor R&D.In contrast, Japan’s nimble and specialized supplier ecosystem gives companies like JSR a competitive edge.

One anecdote illustrates the depth of JSR’s supplier relationships. Several years ago, AU Optronics (AUO) sought to promote its subsidiary Daxin Materials as a substitute supplier for panel photoresists, aiming to replace JSR. A manager at Daxin convinced one of JSR’s suppliers to secretly provide samples, successfully developing a new photoresist and gaining AUO’s certification. However, when JSR discovered this, it immediately ordered the supplier to cease all cooperation with Daxin.

In the end, the supplier’s executive and Daxin’s manager went to AUO’s headquarters together and knelt before its senior executives to apologize. “He would rather kneel than betray JSR,” recalled an eyewitness.

However, with an aging population and a dwindling artisan spirit among Japan’s small and medium-sized enterprises, will this ecosystem that Koshiba has much confidence in soon face challenges?

When asked about these concerns, Koshiba, who is typically candid, offered a more measured response. “We conduct strict audits of our suppliers,” he said, sidestepping our question for the first time.Today, semiconductor materials are a fiercely competitive battleground. Global giants like Merck and DuPont have made major moves to expand their presence in the field. How has JSR managed to stay ahead? Koshiba credited Japan’s network of small and medium-sized suppliers, which he described as unrivaled in quality. “Without them, we wouldn’t be this strong,” he said.

Photoresist is composed of three primary components: photosensitive materials, resins, and solvents. Each of these is further divided into seven to eight subcomponents, which JSR sources from a variety of suppliers. By contrast, vertically integrated chemical conglomerates like DuPont produce these materials internally.

While this approach might seem more efficient, a manager of chemical supplier for the TSMC pointed out to me that large conglomerates often overlook small-volume semiconductor material requirements, prioritizing their larger, more profitable divisions instead. This lack of focus results in slower response times and fewer resources for semiconductor R&D.In contrast, Japan’s nimble and specialized supplier ecosystem gives companies like JSR a competitive edge.

One anecdote illustrates the depth of JSR’s supplier relationships. Several years ago, AU Optronics (AUO) sought to promote its subsidiary Daxin Materials as a substitute supplier for panel photoresists, aiming to replace JSR. A manager at Daxin convinced one of JSR’s suppliers to secretly provide samples, successfully developing a new photoresist and gaining AUO’s certification. However, when JSR discovered this, it immediately ordered the supplier to cease all cooperation with Daxin.

In the end, the supplier’s executive and Daxin’s manager went to AUO’s headquarters together and knelt before its senior executives to apologize. “He would rather kneel than betray JSR,” recalled an eyewitness.

However, with an aging population and a dwindling artisan spirit among Japan’s small and medium-sized enterprises, will this ecosystem that Koshiba has much confidence in soon face challenges?

When asked about these concerns, Koshiba, who is typically candid, offered a more measured response. “We conduct strict audits of our suppliers,” he said, sidestepping our question for the first time.